Pine Valley Golf Club’s past sexism is reflected throughout Camden County

Pine Valley Golf Club, nestled in Pine Hill, Camden County, is a century-old institution often celebrated as one of the top golf clubs in the United States. Unfortunately, it was also a masterclass in institutionalized sexism. In 2023, the club settled with the state over policies that barred women from owning homes on its land unless co-owned with a man and excluded women from membership. These policies are a stark reminder that sexism is not merely an individual failing—it thrives through institutions and policies. To counter this, embracing feminist urbanism in Camden County could pave the way for a more sustainable, equitable, and thriving community.

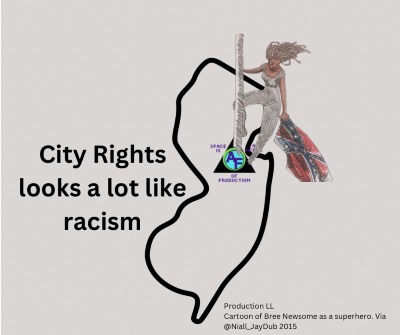

Where sexism restricts housing access, it often intertwines with racism and classism. Camden County is one of New Jersey’s most inequitable regions. Black residents are disproportionately concentrated in Camden City, where the median income is $27,000—the lowest among all racial and ethnic groups in the county. Additionally, 32% of families in Camden County are headed by a unpartnered parent, typically a woman, and these families are often clustered in or near Camden City.

The disparities between the wealthy and the working poor continue to grow, with unmarried women—especially those not partnered with cisgender white men—bearing the brunt of these inequities. In Camden, the median monthly rent is $938. Over the past 20 years, housing costs have risen by over 20%, while incomes, adjusted for inflation, have fallen by nearly 21%.

Current efforts to address these disparities are falling short. A feminist urbanist approach could provide planners, policymakers, and stakeholders with the tools to dismantle institutionalized sexism, which disproportionately affects women. To reduce urban sprawl and use land more efficiently, we must stop segregating housing by socioeconomic and racial classes. Similarly, education facilities, childcare centers, homes, and retail spaces must coexist in mixed-use developments to create sustainable, livable communities. This shift is no longer about personal preference—it is a necessity in the face of the climate crisis.

Feminist urbanism offers a framework for addressing the sexism that fuels racial and economic inequalities. It prioritizes the needs of the community over market-driven interests or the preferences of men. Transportation planning, housing policies, and zoning decisions are still largely designed around the income and schedules of men. By centering planning efforts on the needs of the community and the environment, justice for all becomes a natural outcome. One thing Camden could do is when developing mixed used development make it not only mixed income, but also mixed family types, not every family is a nuclear family and single women exist. Also, it might consider ceasing to use the terms “urban Camden” and “suburban Camden” as all of New Jersey is urban, so those two terms are just not so clever of a way to racialize locations.

Adopting feminist urbanism in Camden County could lay the foundation for a more just and inclusive future for South Jersey.