What the US can learn from Syria about sexism and urbanism

According to the Guardian Bashar al-Assad resigned and fled Syria last night, Saturday, December 7, marking what could be the start of a better future for Syria—especially if the Kurds via the PKK regain their areas.

Why am I writing about this here in a media project set in New Jersey? Oppression begins with how a Metro is shaped and who is allowed in its spaces. Syria is in many ways a warning of what could happen here.

Since 2011, Syrians have endured horrific authoritarian policies under Assad, policies that extended deep into the fabric of even urban life. Assad’s regime weaponized urban development, using it to reward loyalists and punish dissenters. During the civil war, selective reconstruction prioritized pro-Assad areas, leaving opposition strongholds to crumble. Informal settlements, often viewed as hotbeds of people and organizations critical of Assad, were demolished, and property laws like Law No. 10 were manipulated to prevent refugees from returning to their homes.

Growing up in the hypersegregated neighborhoods of Los Angeles, I saw firsthand how urban policies can be wielded as tools of control and suppression. Assad’s tactics, particularly through Law No. 10, exemplify this on an extreme scale.

Law No. 10 may be one of Assad’s most harmful urban policies. It grants the government power to designate “redevelopment zones” and seize property with minimal recourse for residents.

“Law No. 10 contributes to a legal scheme intended to enable the Syrian government to designate land anywhere in the country for redevelopment. Per the law, when an area is designated for redevelopment by decree, authorities have one week to request a list of property owners from local real estate authorities and existing land registries; these authorities are to provide this list within 45 days. Property owners whose names do not appear on the list or are not included in land registries will have one year to make a claim of ownership for the purposes of compensation, as all property owners will be displaced from their properties as a result of the government’s redevelopment plans.”—Tahir Institute

Law No. 10 doesn’t just seize property; it induces sprawl. In Syria, as elsewhere, sprawl serves as a means of consolidating political control over underdeveloped areas.

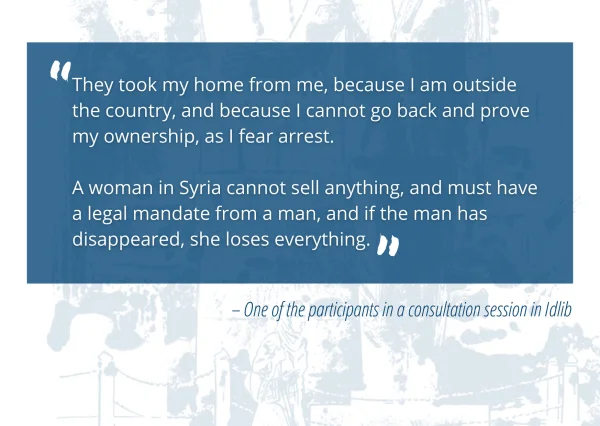

For Syrian women, the harm inflicted by Assad’s policies is layered and complex. Workforce participation increased, but rights diminished. Women, often reduced to beasts of burden, suffered disproportionately under the regime’s punitive measures.

“Syrian women have been paying the highest cost of the ongoing conflict. The punitive and retaliatory approach of the regime, and the return to clan, sect, and religious affiliations in some areas as a result of social and political exclusion, have contributed to the progressive deprivation of women’s civil rights and social entitlements.”—WILPF

While urban women in Damascus and Aleppo fared slightly better than their rural counterparts, they still experienced reduced pay and human rights. Those perceived as politically active faced torture, imprisonment, and disappearance.

“I don’t think the world understands what it means to be a woman living in Syria today,” says Shatha, a survivor of gender-based violence from Deir-ez-Zor.—ArabStates

This remains a developing situation. The United States may yet play a role, however unlikely it might seem. What happens next could redefine Syria’s future which with some luck could be feminist, and perhaps finally end years of suffering under authoritarian rule, which is ironic to look at from the United States with its new elected- President that some have called authoritarian and violently misogynistic.