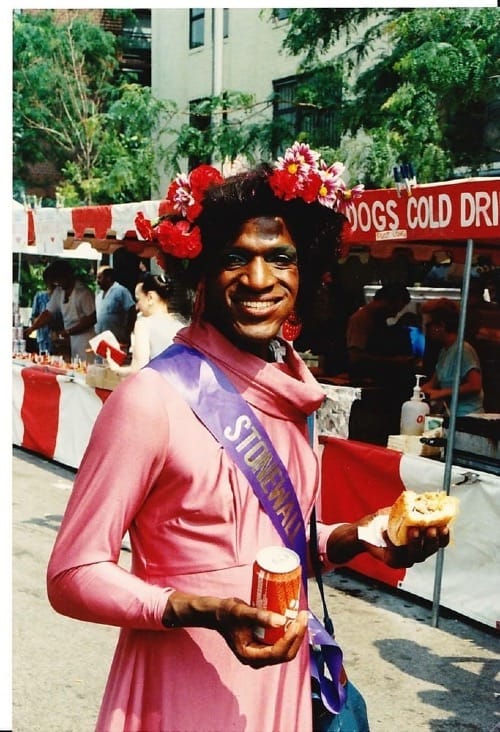

International Women’s History Month at AF presents Marsha P. Johnson, born in New Jersey and a fighter for liberation in the LGBTQI community

Marsha P. Johnson blazed through the streets of 1960s and 1970s New York as a luminary of the gay rights movement, her smile as much a weapon as her wit. She championed homeless LGBTQI youth, fought for those ravaged by HIV and AIDS, and demanded dignity for transgender people in the U.S.

Born in 1945 to a working-class Black family in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Johnson embraced her identity early. By five, she was stitching together dresses from scraps, defying a world that punished her for it. Bullied by classmates and assaulted by a teenage boy, she fled to New York after graduating from Thomas A. Edison High School with $15 and a single bag—her escape pod to self-invention.

In the city, she reclaimed her truth, adopting the name Marsha P. Johnson. The “P,” she quipped, stood for “Pay It No Mind”—a mantra for shrugging off bigots. She called herself a gay “transvestite” and drag queen, pronouns she/her, navigating a family relationship her nephew later described as “close but fraught.” Survival, though, was a daily battle. New York criminalized LGBTQI existence, pushing Johnson into sex work. Clients abused her; police arrested her. She slept in theater seats, diners, and the cramped apartments of friends, yet still carved out joy in thrift-store finery and drag performances. “I was no one,” she reflected in 1992, “until I became a drag queen.”

At 17, Johnson met 11-year-old Sylvia Rivera, a Puerto Rican transgender girl. “She was like a mother to me,” Rivera would say. Together, they forged a bond as unyielding as their glitter crowns. On June 28, 1969, their lives collided with history at the Stonewall Inn. When police raided the bar, Johnson and Rivera arrived to the chaos. “The place was already on fire,” Johnson recalled. Myths swirl about her actions that night—throwing a shot glass? A brick?—but her frontline ferocity is undisputed. For Johnson and other trans women, Stonewall wasn’t just a riot; it was catharsis.

The uprising electrified the movement. Pride marches erupted, and groups like the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) emerged. Johnson joined both but bristled at their exclusion of trans people and people of color. “They told us to go hide our nails in our pockets,” Rivera seethed. So in 1970, the pair founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), sheltering queer youth in a rotting Greenwich Village truck, then a derelict building. STAR House crumpled, but its ethos endured: community as family.

Johnson’s activism soared. She dazzled in the drag troupe Hot Peaches, posed for Andy Warhol’s “Ladies and Gentlemen” series, and rode in Pride’s lead car in 1980. Yet shadows followed. Mental health crises landed her in hospitals; HIV struck in 1990. Still, she preached resilience: “Don’t fear us,” she urged in one of her final interviews.

On July 6, 1992, fishermen found her body in the Hudson River. Police called it a suicide; her community cried murder. The case, reopened in 2012, remains unresolved. At her funeral, crowds overflowed the church, spilling into the streets—a testament to her orbit.

Today, Johnson’s legacy still lights the way to liberation. She endures not as a martyr but as a beacon: a woman who refused to be erased, who taught us to fight—and to glitter—while doing it.

“As long as gay people don’t have equal rights,” she once declared, “there’s no reason for celebration.”